Kitty Wilkinson – A Civic Myth

`Kitty Wilkinson – a civic myth?’

`Kitty Wilkinson – a civic myth?’

This material has been reproduced from a series of articles published between February and May 1972 in Baths Service ‘The Journal of the Institute of Baths Management Incorporated’.

The Author is John Dobie who was, at that time, Principal Administrative Officer in the Further Education Branch of the Manchester Education Authority.

It was whilst teaching history in a Liverpool school that he first came across the Kitty Wilkinson story and doubted its veracity. Mr Dobie, who held a Master’s Degree in Education, very kindly gave permission for `Baths Service’ to use the book in serial form over a period.

`SO THE STORY GOES . . . ‘

The little lady in the white bonnet, the starched dress with its Paisley motif, and the gingham apron, has become enshrined not only in Liverpool folklore and in the windows of the Lady Chapel in the Anglican Cathedral, but also in the history of the development of communal concern in matters of public health and hygiene.

The story goes that Catherine Seward (as she then was) was born in Londonderry on the 24th October, 1786. When she was still a child her widowed mother sailed with the family for Liverpool. But the vessel was wrecked before it reached port, and the crew and passengers had to take to a small boat. Kitty and her mother were both saved but her infant sister, swept out of her mother’s arms by a huge wave, was drowned. Nor was this all that befell them. So violent was the shock to her distraught mother that she later lost both her sight and reason.

The story goes that Catherine Seward (as she then was) was born in Londonderry on the 24th October, 1786. When she was still a child her widowed mother sailed with the family for Liverpool. But the vessel was wrecked before it reached port, and the crew and passengers had to take to a small boat. Kitty and her mother were both saved but her infant sister, swept out of her mother’s arms by a huge wave, was drowned. Nor was this all that befell them. So violent was the shock to her distraught mother that she later lost both her sight and reason.

In 1797, at the age of 11 years, Kitty was sent to work in a cotton mill at Caton, near Lancaster, which belonged to Messrs. Greg who were related by marriage to the eminent Liverpool family, the Rathbones. After working in Caton for seven years she returned to Liverpool to look after her mother. She then spent four years in service, one year with a Colonel and Mrs. Maxwell and three with Mrs. Richard Heywood. In 1811 she quitted service and went to live, once again, with her mother. In order to maintain her mother, Kitty opened a private adventure school (a `Dame’ school). Within a year, however, she was married to John De Monte, a French Catholic sailor. The `Memoir of Kitty Wilkinson of Liverpool’ describes him as a

` very respectable man, and a kind, affectionate husband. He agreed to her stipulation that she was never to be asked to change her religion or her place of worship, and that her children were to be brought up Protestants.’

Her married life with him was very short, as, owing to his frequent absences at sea, they only lived together three months in all. The `Memoir’states that she gave birth to a son who was called John after his father; her second son was not born until after Kitty had become a widow. The circumstances were as follows

De Monte, on hearing of her second pregnancy, decided to return from Canada.

`He immediately sold all he possessed in order that he might send money to assist her. He did not, however, return, as the ship he was in, foundered at sea, and all on board perished.’

Kitty was at this time quite destitute and forced in her altered circumstances to move to a smaller house.

The reduced accommodation curtailed the number of children attending her ‘school’ (at one time she had as many as 93 scholars paying threepence per week – they were taught in a large room, for which she paid an annual rent of £5), and in order to supplement her declining income, she went out to char and also to work in the fields. By this time she was under a considerable strain: her deranged mother, her first child not two years old, the hard labour in the fields, her remaining pupils dispersing, the financial pressures and the imminence of the birth of her second child drove her to a state of near despair. But help came to her from the mistress of one of the houses at which she had charred; with this help she and her child – another boy, Joseph De Monte, – survived, a feat in itself in those days of primitive midwifery!

Her recovery from this confinement, not helped by the news of the death of her husband, was long and tedious, but as soon as she was strong enough she went out to work in a nail factory. Kitty was paid threepence for every one thousand two hundred nails she made; her weekly wage averaged four shillings. As a result of the work, her fingers became badly burned by the hot nails and so terribly blistered and inflamed did they become, that she gave up the job – it lasted for – 12 months.

She was then obliged, most reluctantly according to Mrs. Eleanor Greg Rathbone (1790-1822), to apply to the Guardians for some assistance towards the maintenance of her two infant children.

`Having been born in Ireland, she doubted her claim to relief; with her accustomed scrupulous sense of right, she informed the overseer of every circumstance which she thought unfavorable to it. Her claim, however, was admitted and for seven years she received two shillings a week for her children.’

To supplement this, she once again turned to charring and doing odd jobs in the fields, until she was befriended by the wife of a Mr Alexander Braik, a dyer, who lived in Pitt Street. During the last 18 months of her life, Mrs. Braik suffered painfully and Kitty was constantly occupied in nursing her. When the lady died, her husband presented, as a small token of his gratitude, a mangle to Kitty, and presently she began to take in washing. She now toiled more laboriously than ever, often working round the clock with but little substantial food to sustain her. This was for Kitty a period of grinding poverty and such was her nature that when she did have money or food to spare, it tended to be given to other people in distress.

In 1823, on the 1st December at Holy Trinity Church, Kitty married for a second time. Her husband this time was Thomas (also known as John) Wilkinson, who had been an apprentice in the cotton mill where she had worked as a child (Caton). The story goes that Wilkinson, having come to work in Liverpool as a porter in Mr Rathbone’s cotton warehouse, was walking one day through the grimy Liverpool streets when he heard someone singing one of the old Lancashire songs that he knew so well.

`Listening intently, he seemed to recognise the voice of the singer, and it was in this way that he met again, after so many years, the girl he had loved and lost at Caton.’

` . . . Of course they were married and spent nearly a quarter of a century together in the most perfect harmony.’

At this time Kitty was living in Benison Street in one of the cellar dwellings in which the poor lived in those harsh times. During the years following their marriage the Wilkinson home became a refuge for all sorts of unwanted children and aged folk who had no one to care for them. Kitty apparently shouldered these burdens without a thought, and how she managed must be something of a mystery. At one period she was keeping a family of 14 on £2 4s. 6d. per week, 10 shillings and sixpence of which went in rent and water. Yet for all its lack of luxuries, the Wilkinson household seems to have been a happy one where ample, if plain, meals were provided, and the long summer evenings were passed in playing games, listening to music (?) and reading aloud. In fact, a home humble though it was which attracted the regular visits of teachers from the Liverpool Mechanics’ Institute.

Whittington-Egan thinks that, thus far, Kitty had already lived a truly saintly life of selfless devotion to others, but it was in 1832 when the cholera epidemic broke out in Liverpool, that she was to do her most heroic work. He goes on to say that;

`Day and night this courageous woman flitted in and out of the houses of the sick and dying. She became the ministering angel of the epidemic and apart from fearlessly nursing the sick and helping the overworked doctors, she made every morning sufficient porridge to feed 60 children and gave up her very bedroom so that 20 children whose parents had the fever might be washed and tended there. She contributed sheets and blankets for sick beds from her own slender stock and placed her tiny kitchen, which contained a boiler, at the disposal of her neighbours so that they might wash and disinfect with chloride of lime those disease-laden clothes and bedding which their poverty-stricken owners could not afford to lose. It was in this kitchen of her’s that the idea of a public wash-house first originated.

Fourteen years after the cholera outbreak, a public wash-house was opened in Frederick Street, and Kitty and her husband were appointed as its first superintendents.’

Whittington-Egan continues his story by saying that all that she had done so quietly during the time of the cholera was eventually recognised,

`for it came to the attention of some important local personages. In the same year, 1846, Kitty was summoned to Carnatic Hall where she found many people gathered to do her honour and the Lady Mayoress presented her with a silver tea service, on which was inscribed

‘The Queen, the Queen Dowager and the Ladies of Liverpool to Catherine Wilkinson, 1846.’

Two years later on the 18th January (1848), Thomas Wilkinson died. Kitty lived on for 12 more years after his death. For four years the widow and her son looked after the Frederick Street wash-house until in 1852 it was pulled down in order to erect a larger and better equipped one on the same site. Whittington-Egan says that;

`Mrs. Wilkinson was “compensated” for the loss of her job by being allowed to make and hem all the towels for a new establishment at a salary of 12 shillings a week.’

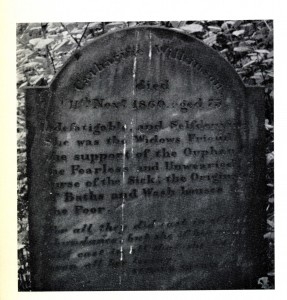

She died, aged 73 years, on 11th November, 1860.

`Her memory and that of “all poor helpers of the poor was perpetuated in the staircase window of the Lady Chapel of Liverpool Cathedral. Kitty is buried a few hundred yards away in St. James’ Cemetery And surely she rests content in the knowledge that she did most wonderfully keep that childhood vow to her beloved friend, Mrs. Lightbody.

And every now and then a few simple flowers, carefully arranged in empty milk bottles, are placed on her grave, doubtless the grateful tribute of the poor who still remember their gallant little champion acid friend – Catherine of Liverpool.’

KITTY AND THE EARLY RATHBONES

It has been necessary in order that one might trace the development of the Kitty Wilkinson `myth’ to retell it, first of all, in a shortened form. Briefly recapitulating, it could be said, leaving aside all embellishments, that she was an Irish Protestant immigrant who came to Liverpool early in the nineteenth century. Her early years were spent almost entirely in the company of her mother, her father, a soldier, died when she was very young. Her mother became mentally deranged as a result of an unfortunate accident whilst they were migrating to Liverpool. Her deprived childhood was one that was more conducive to producing an anti-social type rather than the unselfish and co-operative character that emerged. Her working career was, to say the least, somewhat varied, including work in a nail factory, charring, agricultural labouring, running a `Dame’ school, being an operative in a cotton mill, and the management of a public baths and wash-house. This flexibility in using her labours was not uncommon for her times, as ill-health and the fortunes of trade militated against continuity in employment.

Her marriages were not untypical of those of her station at that time. Her first marriage with a sailor visiting one of the country’s leading ports can be described as a `mixed’ one. Her husband was a French Roman Catholic, Emmanuel De Monte (though variously spelt on the marriage certificate and in the parish baptismal registers) and he does not appear to have spent very much time with her. The `Memoir’ states that it was only three months in all and also that the birth of their first child was in 1815, three years after they were married at St. Peter’s Parish Church. But the baptismal registers at the church tells a slightly different tale.

Christened 18th July 1813. John Demont.

Father . . . Manuel (mariner).

Mother- . . . Kitty. Both of Frederick Street.

As the wedding took place on the 5th October, 1812, and christenings in the Church of England usually take place some four to six weeks after the birth, then it is very possible that Kitty had given proof of her fertility before she and Emmanuel met the Reverend John Pulford at the altar in October 1812. The `Memoir’ also states that when he heard that she was pregnant for the second time, that he was living in Canada and sold up all his possessions to send her money and immediately set sail to join her. Sad to say, the ship is supposed to have sunk, with all hands lost. Now the information for the `Memoir’ was supplied by Kitty to Mrs Eleanor Greg Rathbone. If she was in fact deliberately misleading Mrs Rathbone, a Victorian Unitarian whose views on such immorality could hardly have been `progressive’, then it is also possible that the ship sinking at sea could also have been less than the truth. It is just possible that Emmanuel De Monte like many other mariners, had a wife in every port. Her second son, Joseph, was christened on the 7th May, 1815, the father being given as Emmanuel, but not described as dead, and the mother as Kitty.

Her second marriage, (it could possibly have been bigamous) was to a much more conventional person, a cotton warehouse worker whom she had known when they both worked at the mill at Caton. This marriage to Thomas Wilkinson took place at Holy Trinity Church, St. Anne Street, (built in 1792 under the Trinity Church Act) on the 1st December, 1823. Thomas, who was stated as living at 63 Frederick Street, made a mark in the register – indicating that he was illiterate.

The witnesses were William Fisher and Mary Howell or Powell (the register is somewhat indistinct); this same woman also, along with a Thomas Markhof and Elizabeth Thompson, witnessed Kitty’s first marriage, suggesting that she was probably her closest friend. One puzzling feature is that Kitty, who when she married De Monte had insisted that she was not to be forced to change her place of worship, chose a different Anglican church in which to marry. However, there was a boy christened at St. Peter’s on the 5th July, 1824, whose name was given as `George Wilkinson’ and the parents were listed as John and Catherine Wilkinson of Gibraltar Street.

Thomas Wilkinson came to Liverpool to work in Rathbone’s warehouse. How he obtained this position can be explained by the fact that the mill at Caton where he had previously worked was owned by Rathbone’s brother-in-law, Samuel Greg. In all probability during a time of recession in North Lancashire he had received an `introduction’ and come to seek employment in the rapidly expanding seaport. It would be through his employment at Rathbone’s warehouse that Mrs Eleanor Greg Rathbone would hear of Kitty’s efforts during the cholera epidemic. Thus it was that Kitty and Thomas Wilkinson became one of the channels through which the Liverpool District Provident Society of which Mrs Rathbone was one of the leading lights, passed money and clothes to the poor and afflicted.

So how then did this good but poor woman, who lived in the dockland slums and whose work with the mangle and her general attitude of Christian charity, become the `Queen of the wash-houses’?

To explain this, it is necessary- first of all, to place her story in its historical context – that is, mainly in the Liverpool of the 1830’s and 1840’s. Prior to the great Irish exodus following the failure of the Irish potato crop in 1846, there was already a steady stream of Irish immigrants paying a ten-penny fare on the cattle boats, coming into Liverpool. The expansion of the docks provided a great stimulus to the employment of unskilled labour – firstly to help to build the docks and subsequently to work on them.

Other `immigrants’ into Liverpool at this time were the North Welsh, the Lowland Scots and the English from the rural districts of Lancashire and Cheshire. The demand for low-priced housing was therefore considerable, and not only were cheap back-to-back houses thrown up but also their cellars were sublet to desperate families.

These conditions, which partly explain the `religious difficulties’ experienced in Liverpool (i.e. the competition for houses and jobs leading to a general depression of standards with the consequent communal tensions becoming centred around the religious rallying points – the churches or chapels and their schools), were to change Liverpool from a comparatively healthy place to live in, to that state of squalor and disease which made it the most unhealthy urban centre in the country.

When the cholera, which emanated from Teesside, reached the town, the consequences were disastrous. Between the 12th May and the 13th September 1832, there were within the city 4,977 cases of cholera, of which 1,523 were fatal.’ By the week ending the 13th September, there were but nine new cases, six deaths, 19 recoveries and 67 remaining cases. On the 5th October, the city was declared free of cholera.

Had Kitty Wilkinson’s work during this terrible epidemic been so outstanding, it must surely have come to light immediately. The Liverpool newspapers in 1832 contain no mention of her name or work. There is, however, a letter dated 25th September and published three days later in the Mercury from Dr. W. W. Squires and Dr. J. Hunter Lane. Its purpose was to publicly thank the Protestant and Catholic clergy, the District Provident Society, and Mr Overseer Henshaw for their help during the epidemic.

The Overseer was particularly commended for his;

`economical and judicious management of the Refuge House’.

Dr. Lane and Dr. Squires had been appointed the honorary physicians to the Liverpool Cholera Hospital in May 1832, which had been erected on a large piece of ground between Shaw’s Brow and the Haymarket.

Adjoining it was the former public asylum which had been used as the House of Refuge. Dr. Squires published an article in the Liverpool Medical Gazette about the epidemic in Liverpool. But in the `Memoir’ it is specifically claimed that;

`as the medical men were quite unable to meet the calls upon them, Kitty went to them for advice as to how to act, administered the remedies they ordered and carried back to the doctors intelligence of the results.’

It is therefore strange that the doctors failed to record such co-operation or the local newspapers, ever keen to extract stories of local human interest from the records, failed to hear about her work.

Further, were the medical men quite unable to meet the calls made upon them? Again there is no evidence for this claim. Quite the contrary. The physicians were met with great hostility and were subjected to physical violence – occasions that called forth strong condemnatory leaders in the pages of the Mercury during July. Surely, had they known of such sterling work that Kitty is supposed to have done, they would have mentioned it as a suitable example to the ungrateful poor.

It would appear then that the Memoir’s author and Mrs Eleanor Greg Rathbone, whose manuscript is the chief source of knowledge about Kitty, accepted without corroboration Kitty’s tales about this period. It is therefore possible, in view of her rather `vague’ information about her husbands, children, etc., that Kitty’s tales might have been somewhat coloured, and that Mrs Rathbone, in her middle class naivety, accepted them without reservation.

In June 1837 when the District Provident Society began to run short of funds for their washing cellar, there was printed an appeal to raise money to continue to finance it. (See Appendix A, a copy of the appeal.)

In the appeal there was no mention of Kitty Wilkinson as being the superintendent of the cellar. Yet she was – one can therefore conclude that even in the eyes of the visitors of the cellar, Mrs H. Jones and Mrs William Rathbone (i.e. Eleanor Greg Rathbone), that the work of Kitty Wilkinson was not at that time considered to be worth; of note, nor of particular interest, as an example of working class self-help, to be brought to the attention of the more well-to-do citizens of Liverpool, for whose benefit the appeal was published and who were expected to contribute to the society.

The appeal flopped and the District Provident Society was obliged to withdraw its annual grant of £26. At the same time Kitty Wilkinson, no doubt worn out by her exertions in superintending the cellar, was taken ill and resigned her post . . for which she had received four shillings per week.

Deposited in the Liverpool Record Office is a letter to Kitty from Dr. Joseph Tuckerman of Boston, Massachusetts, which refers to this illness. Tuckerman was a close friend of the Rathbones and during a visit to this country he had visited the wash cellar and also met many of the orphans who had at that time attached themselves to the Wilkinson household. Tuckerman had heard of her illness from William Rathbone, and had subsequently written to comfort her.

Though Kitty’s fame had crossed the Atlantic, it was not until 1844 that she gained some measure of recognition in this country. This was a `contemporary biography’ entitled `Catherine of Liverpool’, which was included in Chamber’s Miscellany of Useful and Entertaining Tracts, and was one of a short series entitled `Annals of the Poor Instances of Female Intrepidity and Industry’.

The tract, which Winifred Reynolds Rathbone thought;

`was written in a quaint, old-fashioned style that makes it rather attractive reading’,

was full of inaccuracies which Miss Rathbone was quick to point out unfortunately in so doing she corrected minor items of detail but based her interpretation on her grandmother’s manuscript and grandfather’s and father’s papers . . . which in their turn were based on what Kitty told them. Thus the errors were perpetuated !

THE HEALTH OF THE TOWN

The next phase of Kitty Wilkinson’s life is not well documented, her period of recuperation was no doubt a long one. At any rate the wash-cellar had ceased to function, and it is to the activities of the town council and the formation of a special committee of that body, known as the Public Baths and Wash-houses Committee, that the story of the development of wash-houses next comes to prominence.

On the 15th June, 1840, a leading article in the Liverpool Albion advocated the use of the Town’s Improvement Fund to provide parks and bathing places. At the town council on the 1st July, Mr Henry Lawrence brought forward a motion on the subject of public baths.

During the course of his speech to the council he mentioned the revival of interest in the subject as a result of the article in the Albion but, like many other politician, reminded his listeners that he had, whilst serving on the finance committee `many years’ earlier, urged the council to provide bathing accommodation for the public, two sites, one in the north and the other in the south end of the city, and that it had been deferred because finances were not available. Referring to his present motion Lawrence went on to say;

`he was sure that this was a proposition which would be supported by gentlemen of all sides in politics. (Hear, hear).’

William Rathbone, in the same debate, said that it was a matter of very great importance and moved its reference to the finance committee for consideration. Councillor Mr Bolton also joined in the debate saying that;

‘he hoped the terms “bathing” was comprehensive enough to include warm water baths.’

A favourable climate of opinion was gradually being prepared in which to carry forward a measure for public baths. On the 10th July the Liverpool Mercury reprinted an article on a `sea-bathing infirmary’ which had first appeared in the Leeds Mercury.

A leading article on the same day said;

`there can be no doubt that such an institution would be productive of extensive good, and we are sure there are very many public spirited and humane individuals who have both the will and the power to lend a hand in the good work. The present time, when we confidently hope the corporation is about to provide bathing accommodation for the public generally, seems particularly appropriate for taking the subject into consideration.’

William Rathbone certainly did take `the subject into consideration’ and went to the lengths of printing a paper on the subject of public baths and wash-houses. (See Appendix B.)

This supported a resolution which he had placed before the town council on the subject and it was circularised to all members of the council. In it he described the living conditions of `our labouring classes’ and the workings of the washing cellar at No. 162 Frederick Street. Rathbone refers to how it declined, viz

`The depression of funds of the Provident District Society and still more the failure of the health of the superintendent caused this very useful charity to be discontinued-for a time only it was hoped, as its great value was thought to have been fully proved.’

Another item of interest in the paper was a reference to the fact that a group of interested people had received a plan for an establishment comprising eight public and two private warm baths, a cellar, where from 200 to 250 women weekly might wash their clothes, a separate cellar for washing infected clothes, a drying stove, a superintendent’s house; with engine, tank, boiler, tubs, etc., which would cost, exclusive of the ground, £720.

The plan was prepared by Mr Franklin who subsequently became the corporation surveyor. (Franklin `came in’ with the Reform Party after 1835.)

Rathbone’s motion on the provision of public baths and wash-houses came before the town council on the 2nd September. It was item 12 on the agenda:

12. ` The following motion, of which notice has been given by Mr Councillor Rathbone:

That a special committee be appointed to consider and report, after such enquiries as may be found necessary, upon the propriety of erections, in three several parts of the town, for baths for the use of the poor, with conveniences by means of cellars, or otherwise, for the washing of their clothes, according to a plan which will be submitted to the council: the financial consideration of the subject being reserved for the finance committee, after the report of the special committee who are to accompany the same with an estimate of expenses.’

The members of the town council who were present, the mayor, 10 aldermen and 30 councillors, agreed unanimously to the resolution and appointed the following members of the council as the special committee.

|

Appointed the following member committee |

of the council |

As the special |

| Councillor William Rathbone | (Reform) | Pitt Street |

| Councillor Henry Lawrence | (Conservative) | Rodney Street |

| Councillor Henry Robertson Sandbach | (Conservative) | Vauxhall |

| Councillor Hugh Hornby | (Reform) | Pitt Street |

| Councillor Richard Vaughan Yates | (Reform) | Pitt Street |

| Councillor Thomas Blackburn | (Reform) | Lime Street |

A brief account of the debate on the resolution appeared in the Mercury on the 4th September. Under the heading `Public Baths’, it said;

‘Mr Rathbone, in bringing forward his motion on this subject, said that as he had already stated his reasons to the council he would simply move the resolution. An anonymous communication had been sent to him from which it appeared that a very large portion of the labouring classes were in a very destitute condition. In some instances a whole family occupy only a single room or cellar. They slept three, four and even more in one bed, and sometimes in a back cellar, in which there was no air except what came from the front one. He concluded his remarks by moving the resolution.’

Councillor Mr Mellor seconded the motion and Councillor Mr John Smith said that he cordially approved of the resolution and hoped that the council would be ready to carry it into effect immediately, for many of their resolutions became dead letters from the length of time that expired before they were carried into effect.

The Albion on the 7th September made some general observations on the state of Liverpool and in particular on the health of the town.

It thought the citizens should be ashamed of the way in which their once healthy town had deteriorated. They reflected that;

`the subject has to a slight extent been opened by Mr Rathbone’s resolution’

and noted the limited objectives of his committee.

Later that day (2nd September) the special committee met but only four of them attended.

The committee acted with such alacrity that one can only presume that Rathbone already had everything ready. Their report with its itemised expenditures, including suggestions for suitable sites, and detailed plans of the type of building to be erected, was approved and passed on to the finance committee for consideration. The presence of the four Reform candidates, three of them being the Pitt Street Ward representatives in which the first wash-house was to be built, and the absence of the two Tory members would leave one to suppose that this committee was merely a rubber-stamp for Rathbone’s scheme.

It is interesting to note that the two wash-houses that were to be built first were on sites near to the north and south corporation schools. These schools, and the accompanying controversy, were very much the concern of two of the councillors on this special committee – William Rathbone and Thomas Blackburn, the two councillors who were the leaders of the Liverpool Reform Party.

The schools and the wash-houses, taken together, seem to represent a genuine attempt at poverty programmes in what we would today call under-privileged, ‘down-town areas’.

Both these `experiments’ involved financial assistance from the town council, though we shall see that when Rathbone and Blackburn commended the wash-houses to the council it was their hope that they would eventually become self-supporting institutions.

The report of the special committee was presented to the town council on 7th October, 1840, when it was Item XI on the agenda.

The council gave their approval to the report and the matter was sent to the finance committee for further considerations.

Two days later the report of the meeting appeared in the Mercury. Rathbone, in moving its adoption and reference to the finance committee, said that he believed that no additional expense would be incurred beyond the erection of the required buildings.

The payment of one penny per week for washing and of threepence, or whatever should be charged for the baths would be sufficient to meet the current expenses.

Blackburn, in seconding the motion, said that one of the strong recommendations of the plan was that it would be a self-supporting institution.

Alderman Evans asked if any example could be mentioned, and observed that it would be consolatory to know that the plan had been tried elsewhere and succeeded.

Rathbone replied that the baths were rather in the nature of an experiment, though he did know of plans to erect them in London and Edinburgh.

With respect to washing, Rathbone instanced the five years experiment in Upper Frederick Street and how it had worked admirably and that 250 women in one week, paying one penny each, had washed their clothes and that with very small apparatus compared with what was proposed. Alderman Earle, who was in the chair, and sitting in for the mayor, said that he thought that there were baths at places where there were steam engines and that the workmen belonging to these particular establishments had the use of them.

Rathbone said that as far as factories were concerned, a brother-in-law of his had one at Lancaster and another at Manchester; there were baths at both, and it was found that they were adopted by the poor with great avidity and with great benefit to health, and at a very small expense.

But all had not been complete harmony as Rathbone’s plan had been attacked in an anonymous letter to the Albion on 29th September. This had spoken of `demoralising the poor’ with such schemes and compared his action with that of his grandfather, Richard Reynolds of Bristol, whose philanthropic gestures had aroused the reactionaries of his day.

Rathbone vigorously defended his grandfather’s works and his own plan in a reply, published in the following edition, seven days later.

The last meeting of the council for the mayoral year, and prior to the annual elections (usually held on 1st November), took place on 31st October. This was traditionally the meeting at which the council tied up any loose ends. The baths question was the first item on the agenda and, as a result of a favourable verdict by the finance committee, the plan for the first new building was approved unanimously.

At the same meeting, notice of a motion regarding the health of the town was given by Mr Councillor Case. He alluded to the number of people mentioned by the Registrar General in a survey of the health of Liverpool who lived in cellars. It was estimated that there was not less than 50,000 people in such accommodation and that many of them were Irish immigrants. The Councillor stressed that diseases were easily communicated to others in these low, damp apartments that lacked ventilation. The motion which he gave notice of was as follows;

`That a committee be appointed to make all necessary inquiries and to take into consideration the subject of inhabited cellars and small dwellings in back courts, with reference to the health of the town and the comfort and convenience of the poorer inhabitants and to report to the council herein with any recommendations that may seem proper to such committee.’

William Rathbone expressed his gratification that Mr Case had brought the subject forward. He said that it had been his intention, if re-elected, to move, in the re-appointment of the committee on the baths, that they should take the wider question of the health of the town also into consideration.

Rathbone’s reservations about re-election, though no doubt an example of his natural modesty, were soon put to the test, for on the day following the successful passage of his motion through the council he was defeated in the Pitt Street Ward annual municipal election by the Conservative, Thomas Toulmin. The margin of defeat could not have been narrower, 189-188 – just one vote. The result, one of great rejoicing for the Conservatives, was very controversial as there were doubts about the credentials of certain voters. However, Rathbone refused to appeal to the mayor to have the voting procedures investigated, though he did not altogether accept the situation with good grace.

The reasons for Conservative rejoicings over the defeat of Rathbone are quite understandable. He was one of the leading members of the Reform Council, he had been instrumental in pushing through the new policies on the corporation schools and in the agitation for the Reform Bill, when discontent was widespread, revolution in the air and Habeas Corpus suspended, his name was on Lord Castlereagh’s special list . . . he was described as `dangerous but has done nothing yet ‘.

At the following council meeting – the first of the new municipal year – a health of the town committee was established and the special committee on public baths and wash-houses was incorporated within it. The subject of wash-houses then disappears from the public stage for the new health of the town committee becomes involved in the provision of sewers, the regulation of courts and the clearing of cellars.

On 1st December, 1841, the surveyor reported that the Upper Frederick Street wash-house would be ready for use about the middle of February, and the committee decided to give its attention to the appointment and salary of a superintendent and rules and regulations for the wash-house. By 14th February, 1842, the health of the town committee no doubt having received a further intimation from the surveyor that the Upper Frederick Street baths were approaching completion, salaries of £60 per annum for a superintendent and £30 per annum for a matron were subsequently recommended.

On. 1st April, the committee was notified that the wash-house and baths was ready for use.

They resolved that an advertisement be inserted once in each of the Liverpool newspapers for a competent person and his wife for the posts of superintendent and matron.

Testimonials were to be delivered to the town hall on or before 11th April. At the next meeting (14th April 1842) a sub-committee was appointed, consisting of Councillors Yates, Cooper, Bright, Edwards and Kilshaw, `for the purpose of opening and examining the several applications and testimonials, and that they be required to report at an early date’.

This sub-committee in effect consisted of all those health of the town committee members who attended 14th April meeting with the exception of the committee chairman, Robertson Gladstone.

By 20th April, 1842, a short list of 11 had been compiled from 104 applications. On that date Andrew Clarke and his wife were selected `as proper persons to fill the situation’.

They were required themselves to give a surety for £100 and to find two other people willing to stand surety for them for £50 each.

The committee further decided to inspect the premises and to see for themselves if in their opinion the baths were in a state of readiness for immediate occupation and use.

At the town council meeting on 6th May, 1842, item nine on the agenda was a resolution from the health of the town committee:

‘Recommended that Andrew Clarke and his wife be appointed keeper and matron of the baths and wash-house in Frederick Street.’

The resolution was agreed unanimously.

I have dwelt at some length of the question of this appointment in order to clarify certain misconceptions that have arisen.

The evidence clearly demonstrates that

(1) The first public baths and wash-house in Liverpool was opened in 1842 on the 28th May and not in 1846.

(2) That Andrew Clarke and his wife, and not Kitty Wilkinson and her husband, had charge of it.

The evidence also helps to refute, as far as can be reasonably established with the existing information available, the imputations made in `The Memoir of Kitty Wilkinson’.

It is stated re the appointment that;

`It was thought by the friends of Catherine Wilkinson that her claims to the superintendence and management of this establishment were very strong, but other interests prevailed and hers were set aside till some time afterwards.’

`But other interests prevailed’ seems to ignore the fact that this public position was put out into open competition.

The fact that it was widely advertised in all Liverpool newspapers (whatever their political persuasion; that it attracted 104 applicants, that a special subcommittee sifted them; all these factors point to it being an appointment that was open and above board.

It is strange, therefore, that the Rathbones, the so-called local champions of `Reform’ should castigate such an obviously democratic appointment. Perhaps they felt that as the initiative was William Rathbone’s, then perhaps the appointment should be his for the giving?

The plain fact was that he was out of power and that the new Conservative council was in no mood to pander to his wishes. In the municipal elections of November 1841, he had attempted to get back on the council, this time for the Great George Ward. He was unsuccessful and took the reverse rather badly. In an address to the electors of the ward, published in the Liverpool Mercury on 5th November, 1841, he attacked;

`the virulent bigotry of the clerical and political leaders of the Conservative Party’

and hinted that their success was aided by bribery, ` treating’ and intimidation.

The Upper Frederick Street establishment seems to have got quietly and efficiently underway. A news item in the Liverpool Mercury on 3rd June, 1842, read as follows;

`Public baths and wash-house. The building in Upper Frederick Street, which has been fitted up at the expense of the corporation for the convenience of inhabitants, is now open to the public daily. The terms for cold and warm baths are exceedingly reasonable and the use of the wash-house and drying place may be had for a mere nominal charge. We have no doubt that this place will prove a great convenience to the inhabitants of the densely populated neighbourhood in which it is situated, and will do much, if its advantages are duly appreciated, to improve the health and appearance of the humbler classes of society.’

On 5th August, 1842, the Mercury gave space to a correspondent who wished to direct the attention of the public to the cheapness, cleanliness and the exclusive accommodation of the baths. The insertion was obviously designed to attract middle class patronage and it described the privacy of the baths – ` each neatly partitioned, with a door which can be locked or bolted at pleasure’.

On 2nd September, 1842, the Mercury published an interim report on the corporation baths and wash-house.

`It is with pleasure we state that these baths are now in a fair way of being duly appreciated by both the middle and humbler classes of our townsmen – more particularly the latter. During the past week, 439 persons attended them, and when we state that there are in the establishment only eight bathing rooms, we think that the expectations of those philanthropic individuals who originated this boon for the humbler orders of our townsmen have been realised and that their advantages are every day becoming more apparent.’

The article went on to urge the erection of similar baths in other parts of the town as it had been ascertained that people travelled considerable distances to use the facilities. But by the time of the health of the town committee’s report to the town council on 29th October, 1842, there was a move to increase the charges for the baths from one penny to two-pence for a cold bath, and two-pence to four-pence for a hot bath.

During the first four months nearly 5,000 people had visited and bathed in them.

After discussion on the propriety or impropriety of raising the charges, the motion was referred back for further consideration. Clearly many Conservative members were not too cost-conscious at this stage and saw its beneficial effects for the `humbler classes’.

Plans went ahead for the erection of a second wash-house in Paul Street, adjacent to the North Corporation School.

The second annual report presented on 23rd August, 1843, to the health of the town committee, had been satisfactory and a report from the surveyor contained plans for the new establishment; by 6th September the matter had been passed on to the finance committee and the building programme appeared to be rolling. But progress was slow and by 3rd June, 1846, there were numerous complaints in the register at Frederick Street from bathers who came from the north end of the town, about the delay at completing Paul Street.

The subcommittee, which was dealing with the project, regretted that;

`so much of the finest season of the year will have previously passed away before their completion’.

However, they were quite sure that the baths would be ready for opening by the end of July.

APPOINTED

The weekly supplement of the Liverpool Mercury, issued on 3rd July, 1846, described the new establishment as;

`a neat, modest-looking edifice of the Tudor-Gothic style of architecture, 168 feet long and 57 feet broad, including a committee room ‘. The architect was the corporation surveyor, Mr Joseph Franklin, the contractor a Mr Thomas Haigh and the total cost for the new building £6,500. Such was the delight with the new building by the sub-committee that Councillor Mr Tinne said he ` would propose a motion for the erection of an additional number of baths on the same principle as those in Paul Street’.

Alderman Earle said he hoped to see a great extension of the scheme.

`Nothing could be more conducive to the health and comfort of the inhabitants of the town as such establishments for bathing and washing.’

When the town council met on 2nd September, Councillor Tinne’s motion on the provision of more baths and wash-houses was debated. He proposed the erection of one to cater for the Mill Street, Sefton Street and Toxteth Park area. He said that this area was densely populated and as poor as anywhere in the city.

Councillor Mr Parker, in a speech reminiscent of one he made during an education debate, said he hoped that baths and wash-houses would be erected in every ward in the town. Councillor Mr G. H. Lawrence was even more ambitious proclaiming the need for a crash-building programme rather than erecting them one at a time.

But the more immediate problem facing the sub-committee on public baths and wash-houses was the appointment of a superintendent and a matron for the Paul Street establishment, and it is at this stage that Kitty Wilkinson and her sponsor, William Rathbone, reappear on the scene.

The sub-committee on 3rd June, 1846, had reviewed the good progress made at Frederick Street over the first four years. In their minutes, included in the health of the town committee Minutes for 1846, they said that they;

`have much pleasure in observing that much of this gratifying result is owing to the unwearied zeal and assiduity of Mr and Mrs Andrew Clarke, the superintendent and matron respectively – of whose attention also to the comfort and convenience of the frequenters of the establishment repeated mention has been made to the sub-committee’.

At the same time notice of the need to consider the appointment of staff for Paul Street was given and it was decided that all members of the health of the town committee should be informed so that they might be present at the next meeting when the matter would be raised. This came six days later, on 9th June when it was unanimously resolved to make the Clarkes superintendent and matron at Paul Street at the increased salary of £120 per annum.

The committee further resolved to replace the Clarkes and the appointment was to be considered in 14 days’ time, on the 23rd June. All the members of the committee were to notify all who had approached them in connection with a baths appointment, and all the people who applied in 1842 were to be similarly notified. There was to be no public advertisement this time.

In the previous November elections (1845) Rathbone had been re-elected to the council in the `safe’ Reform Ward of Vauxhall. On 1st July, 1846, he had cause to be printed a testimonial on behalf of Thomas and Kitty Wilkinson for circularisation of the members of the town council. (See Appendix C.) Clearly this time he was leaving nothing to chance and was backing Kitty openly and strongly. He said;

`The singularity of the case must be my excuse for bringing the application of Mr and Mrs Wilkinson for the situation of superintendents of the baths and wash-houses in Frederick Street, before the members of the town council in this uncommon manner, instead of confining myself f to giving testimony in their favour in the committee, with whom the recommendation to your appointment naturally rests.

He then proceeded to speak of her talents for management and economy, her ` national recognition ‘ in the Historical Register (an article in the January edition 1845, in all probability supplied by Rathbone himself, and possibly with this appointment in mind), her fearlessness during the cholera outbreak, and finally he spoke of the fact that when the original machinery had been installed at Frederick Street, the engineer who had been responsible for its installation, had lodged with the Wilkinson’s, and that Thomas Wilkinson had observed what was going on and how the machinery worked. Perhaps, though, Rathbone’s real motives are revealed best when he said:

`I am anxious about it for its effect upon the poor, as encouragement to follow her example.’

He was no doubt fearful of a revolution as were many Victorians at this time, for this was the period of Chartist agitation, economic depression and the potato blight in Ireland. But it is in this ` public ‘ testimonial that Rathbone in his desire to help Kitty Wilkinson, prepares the way for the `myth’ building that was to follow. He says;

`I would appeal to you whether the institution itself, owing its origin to her- benevolent and self-denying activity, and its prosperity, and subsequent adoption by the corporation, to her clever management, does not give her a claim above other applicants, if she and her husband are found fully competent to carry it on.‘

I feel that he over-emphasises what she did and underplays the work of the District Provident Society and, more particularly, his own part. Certainly the Liverpool Mercury recognised the important part that he had played as early as 1842. This is instanced in their column ` Replies to Correspondents ‘.

`Corporation Baths, Frederick Street. ” . . . It would be idle to comment on the great advantages of bathing as regards health or for the value of the boon conferred or the public; but it may be as well to remind our readers that for it the town is principally indebted to Mr William Rathbone, a gentleman whom, much to his honour, Tory papers delight in abusing “.’

Rathbone’s efforts were not in vain. On 7th July he was appointed to the sub-committee of five councillors, who were to read the 12 applications and to recommend the three most suitable to the health of the town committee. Their recommendations were discussed on 14th July, 1846, and it was resolved that Thomas and Catherine Wilkinson be recommended to the town council for the appointments. They, like the Clarkes, had to put up bonds for £200 and find two other sureties of £200. The Clarkes’ appointments were confirmed by the town council on 5th August and the Wilkinsons’ on 2nd September.

KITTY’S SUPERINTENDENCY

Thomas Wilkinson died on 14th January, 1848, barely 17 months after being appointed superintendent. That his end was near must have been apparent to Kitty for some time for on 13th January, 1848, the health committee (as the health of the town committee had now become) considered a memorial from her requesting to be allowed to continue, with the assistance of her son, the superintendence of the Frederick Street Baths.

We have seen how much sought after these positions were, and the same meeting also received a request for the post from a Thomas Chapman, all this, nine days before Thomas Wilkinson died and 13 days before he was in his grave. Whilst the sub-committee on the baths approved Mrs Wilkinson’s memorial, it was thought necessary to the health committee to arrange for the baths visitors (i.e. the sub-committee including Rathbone) to consider both applications. They reported on 27th January, 1848, thus;

`That having considered the applications of Mrs Wilkinson and Thomas Chapman for the situation of superintendent of the Upper Frederick Street Baths, they recommend that in consideration of the good work of Mrs Catherine Wilkinson in establishing the practicability of the system of baths and wash-houses and the important benefits of their adoption, from actual trial, sloe be recommended to the committee to continue as the superintendent of the said baths and that it be left to her to obtain a suitable person, subject to the approval of the committee, to undertake the official duties of her late husband, and that she be paid the same amount of salary as was paid to her late husband and herself jointly. That the testimonials of Thomas Chapman are highly satisfactory and they recommend the same to be retained for future consideration.

The phraseology is typical of Rathbone and I have no doubt that he was responsible for the decision and the wording of the minute.

Mrs Wilkinson’s superintendency did not, however, last very long. The Public Baths and Wash-houses Acts of 1846 and 1847 had given local authorities borrowing powers to facilitate the establishment of such places, Liverpool’s building programme included the Cornwallis Street Baths and the rebuilding of the Frederick Street washhouse.

On 22nd April, 1851, the Frederick Street wash-house was closed.

Mrs Wilkinson stayed on and continued to receive her salary but had no other duties but that of caretaker.

The methods of book-keeping and the honesty of the money-takers at the various establishments began to cause the town council considerable trouble. In 1852 it was decided to separate the administration of the baths and public wash-houses from the other matters concerning the health of the town, and so on 9th February a baths committee of the town council was set up. On 23rd August, 1852, this committee resolved;

`That the services of Mrs Catherine Wilkinson be dispensed with, the building in Frederick Street being required for the purpose of enabling the contractor to carry on the works, and that she be allowed four weeks wages in lieu of notice, on condition of her leaving the premises within a week.’

This resolution had been made necessary because of a decision made, at a previous meeting on 28th July, 1852, to accept a tender by William Tomkinson of £7,187 to build a new wash-house in Frederick Street and to convert the wash-house at Cornwallis Street into a bath.

The new Frederick Street Baths were opened on 1st May, 1854, and some eight weeks earlier, on 6th March, John Clarkson and his wife had been appointed superintendent and matron at the combined salary of £ 104 per annum. This appointment was to a great extent inevitable as Kitty was now nearly 68 years old and there is no mention of her son at this stage.

On 12th April, 1854, at the town council it was moved by two Reform councillors, Mr Holt and Mr Hornby, both friends of William Rathbone and resolved unanimously by the council:

`That it be referred to the baths committee to take into their favourable consideration the case of Mrs Wilkinson with a view to affording her some employment or remuneration for the public service she has done by instituting wash-houses in Liverpool.’

The baths committee met on 17th April and the Minutes record that:

‘The committee proceeded to consider the resolution passed at the last meeting of the council, and referred to this committee being the case of Mrs Wilkinson Upon full investigation it appeared that there was no situation which could be offered to her, and that this committee had no fund at its disposal out of which to grant any pecuniary allowance But in consideration of her’ former usefulness and meritorious services it was resolved;

`That it recommended to the council to allow her the sun of 12 shillings per week during their pleasure.’

When the town council on 3rd May, 1854, considered the proceedings of the baths committee, they could not accept the recommendation to allow her 12 shillings per week as they had been advised by the town clerk (whose salary was then £2,000 per annum !) that they did not possess the legal powers to do so. The council therefore resolved to refer it back to the baths committee with instructions to find some employment for Mrs Wilkinson which she is capable of performing.

On 12th June, 1854 the baths committee found their way around the problem and engaged her as mender and hemmer of towels at the salary of 12 shillings per week. Whilst it would appear that this was in effect a pension and that very little was expected of her, there is an entry in the baths committee Minutes that does show that she was from time to time called upon to do some work. The entry reads;

`Resolved that 500 linen cases be purchased from William Ackers at the rate of nine-pence each and that Mrs Wilkinson he directed to make them up into towels for the use of the bath (the new Frederick Street ones).’

THE DEATH OF KITTY WILKINSON

The next occasion that Mrs Wilkinson’s name appears in the baths committee Minutes is on 12th November, 1860:

`The chairman (Councillor Thomas Wagstaffe) reported that Mrs Catherine Wilkinson died on 11 November inst.’

`The chairman (Councillor Thomas Wagstaffe) reported that Mrs Catherine Wilkinson died on 11 November inst.’

There was no resolution of regret or sympathy recorded. The town council was equally remiss; there was no reference to her at their meetings on 14th November and 5th December. One might have thought that their memories would have been stirred for on 5th December there was a memorial from Ratepayers, Inhabitants and Medical Practitioners petitioning for the erection of public baths in Creswell Street to cater for the Everton area. This was agreed and £4,000 made available for an immediate start. Nor did her death arouse wide notice in the Liverpool press. The 17th November, 1860, edition of the Liverpool Chronicle noticed the death of a Mr Griffiths `an early member of the Reform Council’ and also of Mr Richard Rathbone (cousin of William Rathbone), of whom it said;

`He was so well known and deservedly respected in this town . . . he now sleeps with other Liverpool worthies in the Ancient Chapel at Toxteth.’

But it was left to the Liverpool Mercury – and one would suspect – to William Rathbone to make good this oversight, viz:

`The Death of Catherine Wilkinson – the Originator of the Wash-houses.’

`This humble but not unknown philanthropist died on Saturday last at the age of 73, and a highly respected correspondent has sent us the following notice of the deceased – a tribute to her memory emanating from one who has an instinctive appreciation of all that is good and generous:

`”It may be well for those of small means as well as those more largely endowed occasionally to review the respective responsibilities of the position in which they are placed, and to take note of what may be accomplished with very small means but a very large heart. This was eminently the case in the humble individual whose death this day we record. The good deed was sown at a very early age by her attending upon an infirm old lady while going her rounds to relieve the sickness or sorrows of the poor. The seed fell upon good ground and produced art abundant harvest through her long and useful life, during which her poor neighbours were always sure of her sympathy and advice, and such aid as her small means but self-sacrificing energy could make available. As to her own necessities which so circumstances must often haze been pressing, she was remarkably unrequiring and reserved During the uneventful season of the cholera in this town her efforts (fearless of risk to herself) were unceasing both by day and by night and they were rendered the more valuable by her practical knowledge and inventive power to meet emergencies as they arose. It was during this period that .she originated, in her own cellar, the plant for wash-houses for the poor which have since been generally adopted. Though labouring for her daily bread, yet site and her husband (who died some years before her) at different times received many orphans in their dwelling, with no claim on them but their destitution, taking charge of them with parental care until able to support themselves or otherwise provided for. In a truly Samaritan and Christian spirit her efforts to relieve knew no limit but in her power to serve. The widow’s mite was trot unfrequently all of this world’s wealth which she had to give.” ‘

This account of her death was reprinted in the weekly edition of the Mercury on Saturday, 17th November, with the following additional paragraph;

`The remains of the deceased were interred on Wednesday afternoon at St. James’ Cemetery and amongst those present was Mr William Rathbone, whom the deceased had served for nearly half a century.(!) Though she had no child of her own to see her laid in the grave she had many that could well be called (as she has called them) her own, having brought up many orphans in her time, and there were many of her adopted children present. Mr Shimmin of Pitt Street had the conducting of the funeral.’

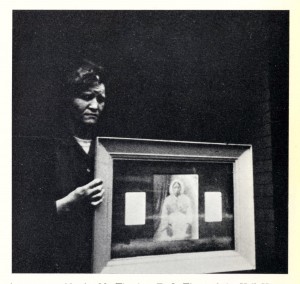

THE PHOTOGRAPH

Thereafter the memory of Kitty Wilkinson for most Liverpudlians faded from view and it was not until 11th March, 1909, that her story regained the public’s attention. The occasion for this was the receipt by the then chairman of the baths and wash-houses committee (Alderman W. Roberts) of two photographs of Kitty Wilkinson. They had been sent to him by Mr Theodore F. S. Tinne of the Hall House, Hawkshurst, Kent, who was the son of the first chairman of the baths committee (as constituted in 1852). Mr Tinne, who was ‘putting his affairs in order’ wrote:

‘Herewith I send you two photographs of Catherine Wilkinson; they both have writing on their backs, telling some history of her. I hope the portraits will be preserved in a way worthy of the noble Liverpool heroine they represent.’

PHOTOGRAPH OF THE PHOTOGRAPHS

The baths committee then had read to them by Mr Court, the baths superintendent, an extract from the book of James Newland, who was appointed borough engineer in 1846; written in October 1856, it said:

The baths committee then had read to them by Mr Court, the baths superintendent, an extract from the book of James Newland, who was appointed borough engineer in 1846; written in October 1856, it said:

‘In 1832 when the cholera ravaged the town, the necessity of cleanliness as a means of arresting or abating the plague became apparent; but poor families huddled, healthy and sick together, often in a single apartment, and that art underground cellar, had not the means for personal cleanliness and still less for washing their clothes and bedding, and thus nothing could be done by them to prevent the spreading of the infection. It was left to one of their own class and station, Mrs Catherine Wilkinson of Frederick Street, Liverpool, to provide a remedy. She, the wife of a labourer, living in one of the worst and most crowded slums of the town, allowed her poorer neighbours, destitute of the means of heating water, to wash their clothes in the back kitchen of her humble abode, and to dry them in the covered passage and backyard belonging to it.

`Aided by the District Provident Society, and some benevolent women, this courageous self-denying woman contrived to provide the washing of, on an average, 85 families per week. Poor people contributed one penny per week towards the running expenses.

`The great supporters of Mrs Wilkinson in her praise-worthy efforts were Mr and Mrs William Rathbone. To their fostering care we owe the recognition of her services, and the institutions to which these gave rise. Here then was the germ of public wash-houses institutions called into existence as a means of palliating a great evil.’

Alderman Roberts, after thanking Mr Court for reading the account to the committee, commented upon the unique gift of Mr Tinne, and said:

`Kitty Wilkinson was evidently one of Liverpool’s heroines who did a great amount of good in her day and generation. It was a great pleasure to the committee to become the possessor of a photograph of the pioneer of baths and wash-houses not only in Liverpool, but in the Kingdom. Liverpool would hold in grateful remembrance such an honourable woman.’

Thus local pride in achieving a ‘first’ now enters into Kitty’s story. Councillor Mr King, who seconded the vote of thanks to Mr Tinne for his gift, said:

`This was an instance of one of the humble citizens doing a good work. They (the committee) ought to be proud that a woman of such humble origins had been able to do so much for Liverpool. If she had been a rich woman, a monument would have been raised to her. (Hear, Hear).’

Other members followed with similar remarks and a vote of thanks was passed, and it was agreed that the photograph should be enlarged and a copy hung in each of the baths and wash-houses.

It was shortly after this revival of interest in Kitty Wilkinson that the first stage of the Anglican Cathedral – the Lady Chapel – was being completed. At that time, discussions were being held to decide who should be commemorated in the windows of the chapel. In the pamphlet entitled `Noble Women : Windows in the Lady Chapel’, the compiler, C.F.H.S., states that Sir Frederick Radcliffe, who was concerned with the promotion of the cathedral from the start, wrote in the Cathedral Committee’s Quarterly Bulletin for December 1944, that:

`These windows do not adjudicate prizes for holiness or priorities in merit. They exhibit typical examples . . . Of course no one would say that they were the only possible or the best examples throughout the ages of a particular virtue. Two rules were among those adopted in making the choice –

(a) that no living person should be selected as the example of a particular virtue, and

(b) that whenever a woman connected with Liverpool or district happened to be eminently suitable, she should be chosen.’

Sir John Marriot, the Oxford historian, when looking at the original windows was asked what he would say about them as a historian; he replied:

`First, it is interesting and valuable to a historian to learn what kinds of people were admired at the time when Liverpool cathedral was begun. All the women here depicted were admired between 1904, when the foundation stone of the cathedral was laid, and 1910 when the first portion of the Lady Chapel was opened. Secondly, see the wide variety of thought and outlook represented by these different women.

`Elizabeth Fry’s views must have been very different from those of Lady Margaret Beaufort. English people, however, do not ask what views did these people hold. They ask, what did they do to help the world? All these women in one way or another helped the world. I call these very English windows.’

C.F.H.S. goes on to say that the windows commemorating Noble Women of Modern Times has been one of the features of the cathedral found most interesting by visitors.

`Innumerable addresses on subjects taken from them have been given by leaders of bible classes, study circles and women’s organisations. Now when the portraits are about to be replaced in new glass (in the summer of 1951) the lives of these noble women have been freshly studied, and this little booklet has been prepared, both as a souvenir for the interested visitor and as a small source of information and idea for those who desire a few lecture notes.’

Unfortunately, however `freshly studied’ repeated the fact that:

`Later she and her husband were appointed the first caretakers of the first public baths and wash-houses, built because of her example.’!!

Some two years later, the Liverpool Daily Post mentioned Kitty’s work in an article to commemorate her birthday, 24th October. Once again the error re the date of the opening of the first establishment and the personnel who superintended was made, viz

`During the cholera outbreak, Mrs Wilkinson – Catherine of Liverpool – as she became widely known, not only bore a foremost part in the nursing of the sick but carried the self-abnegation to the extreme degree of sacrifice by washing the bedding and clothing of the afflicted in her own house. Her noble example and endeavour were the direct instigations of the movement which culminated in the establishment of public baths and wash-houses. The first of these buildings was opened in 1846, with her and her husband as the first supervisors. A window is appropriately dedicated in her honour in the Lady Chapel of Liverpool cathedral.’

CIVIC WEEK

Interest again revived in Kitty’s work in 1925. The public baths and wash-house (the one rebuilt in 1852) in Upper Frederick Street was judged to be inadequate for the times and a new building was erected in Gilbert Street to replace it. The Liverpool Daily Post and Mercury reported the annual inspection of the public baths and washhouses, which took place on the 10th September. The opening of the Gilbert Street wash-house was the central incident of this annual inspection. It was officially opened by Alderman J. Dowd, J.P. and amongst the party of civic dignatories was Eleanor Rathbone. After listening to a speech extolling Kitty’s virtues which emphasised that the building was to be called after Kitty in order to perpetuate her memory as the founder of such institutions `not only in Liverpool but throughout the country’, Eleanor Rathbone, in a comment to the Press said : `I used to hear a great deal about Kitty Wilkinson when I was a child.’

More was heard also of her when, three weeks later, the Baths and wash-houses committee published a brochure about their new washhouse. But it was the following year which saw the most concerted civic efforts to publicise Kitty’s work. The occasion was Liverpool’s Civic Week of 1926 (the week opened on Saturday, 16th October.)

The Liverpool civic weeks of this period were mainly the work of the Lord Mayor’s secretary, Percy Corkhill, assisted by the deputy city librarian. George H. Parry (who became chief city librarian from 1929 to 1933;. Known as `Liverpool’s Pageant Master’, Corkhill’s aim was `to make a modern city gay’.

The programme for the start of Civic Week 1926 consisted of the Lord Mayor, Councillor F. C. Bowring `opening five pages of Liverpool History’. The ‘pages’ illustrated events of special interest and the Lord Mayor and his retinue visited different parts of the city to witness mini-pageants and to deliver suitable homilies to the citizens. The five episodes were the Granting of the First Charter, 1207 (Castle Street), the Opening of the First Ferry, 1292 (Pier Head), the Foundation of the First Charity Buildings, 1728 (Bluecoat Buildings), the First Public Baths and Wash-house, 1832(!) (Gilbert Street), and the opening of the Anglican Cathedral, 1924 (St. James Road – tree planting).

Episode IV at Gilbert Street was designed by Corkhill as follows:

CIVIC WEEK, Oct. 1926

EPISODE IV.

The Opening of

The First Public Baths and Wash-house,

Frederick Street (1832).

| 11-00 to11-30

11-30 |

The Boys Brigade and Soldiers dressed in the uniform of the Period will line the enclosure.” Kitty Wilkinson ” (Miss Marie Lohr) and her companions will assemble in the wash-house.Selection of Music by Bibby’s Band.Two boys will bring two forms out of the wash-house and place them in position and eight boys and eight girls will sit on the forms.When the Band ceases playing a call will be sounded on trumpets –” Kitty Wilkinson,” preceded by a small boy and girl will leave the ” Kitty Wilkinson wash-house,” Gilbert Street.The Lord Mayor and the Lady Mayoress will drive up and on alighting they will shake hands with “Kitty Wilkinson.”“Kitty Wilkinson” will then give a lesson to the class, eulogising the life and character of this Noble Woman, after which they will rise and sing the Old Folk Song : “Dashing Away with the Smoothing Iron.”As the singing is finishing two working women Miss Muriel Randall and Miss Diana Wynyard) leaving the Baths carrying baskets of unwashed linen will walk up to Kitty and place them on the ground and the three women stand together, Kitty slightly in front.The Lord Mayor, Lord Derby and The Right Hon. T. P. O’Connor will address the gathering.

The Lady Mayoress will then make a short speech : “As my predecessor of old, Mrs. Lawrence, presented in t8¢6 to Kitty Wilkinson a silver tea-set I have now the pleasure to present you with a miniature replica inscribed as follows (reads): `Presented to ” Kitty Wilkinson” (Miss Marie Lohr) by the Lady Mayoress (Mrs. E. W. Hope)-Civic Week Pageant, October, 1926.’ “Kitty Wilkinson ” will reply-finishing up with the words ” My Lord Mayor – to my washing-to my washing.” “Kitty Wilkinson” bows and led by the two women and the school children returns to the wash-house. The Band will play the ” National Anthem ” and the Lord Mayor and the Lady Mayoress will leave. |

The Lord Mayor in his speech, said

`Kitty lived in a squalid neighbourhood, no doubt much worse than it is today, but she was a woman of fine inspiration, courage and perseverance. Without publicity and without hope of reward she laboured and though she worked in obscurity, she eventually attracted to her work the attention and help of one of our most honoured citizens – Mr William Rathbone. As you know the name of Rathbone has for generations been associated with nursing and other philanthropic movements in this city, and I now pay my respectful and sincere tribute to that family.’

In an interview in the Liverpool Evening Express, 19th March 1935, Corkhill, who was awarded a C.B.E. for his public services, reminisced about how he secured Marie Lohr to ` play’ the part of Kitty Wilkinson.

`I wanted for one of my pageants, a woman to take the part of Kitty Wilkinson, the woman who founded the great wash-house system. Who could I get? Marie Lohr was due in Liverpool during the week. I dared – I wrote to this distinguished actress who was away on tour in the country, and much to my astonishment and joy she consented….’

Corkhill finally observed

`What more natural, therefore, that the modern world should celebrate, its great works and progress by pageantry?’!!

But Percy Corkhill was not the only person interested in Kitty Wilkinson. The following letter appeared in the Liverpool Daily Post.

d Gambier Terrace,

1st October 1926.

`To the Editor.

Sir,

I have been wondering whether in Civic Week preparation a small but not insignificant piece of commemoration could be achieved. The grave of Kitty Wilkinson in St. James’s Cemetery, is strangely neglected. Everybody’s business is nobody’s. Still, perhaps the trustees of the cemetery might deal with it by reciting the words, clearing the weeds and putting the stone upright. I daresay they would if they thought of it. Perhaps this suggestion may reach . . . I hope so.

Yours etc.,

G. F. Howson.’

Of Archdeacon Howson we will hear more later.

In the following January (1927), Messrs Henry Young and Sons Ltd. Booksellers, of 12 South Castle Street, Liverpool, announced that they would be publishing the `Memoir of Kitty Wilkinson of Liverpool 1786-1860′. In the pre-publication promotional release it was claimed that it was written about the year 1835 and was now to be edited by Herbert R. Rathbone with a foreword by the Right Honourable T. P. O’Connor, P.C., M.P. The manuscript had ` recently been discovered among papers left by Mrs William Rathbone (1790-1882) and although she was not the author, it was written by a member or friend of the Rathbone family, from extensive notes made by Mrs Rathbone during her frequent intercourse with Kitty Wilkinson. It is the only known contemporary ` Memoir of a woman whose distinction is of more than local importance ‘.

The initiative for publishing the `Memoir’ came, as far as one can judge, from the Rathbone family. The Preface of the book said:

‘The inclusion of Kitty Wilkinson among the noble women to whose memory a window has been placed in the Liverpool Cathedral, and the great interest shown by the Liverpool public in the Kitty Wilkinson tableaux during Civic Week, justify, it is thought, the printing of the following Memoir.’

The present head of Henry Young and Sons Limited (Booksellers) is `pretty certain that the initiative for publishing would come from some members of the Rathbone family’. All the firm’s records for the period and the remaining stock of the two Kitty Wilkinson books (the 1910 and 1927 publications) were destroyed in the air raids of 1941.

As the firm was first and foremost booksellers rather than publishers, it can be presumed that not only would the initiative come from outside the firm, but also guarantees to cover costs would have been required.

Thus on Friday, 1st April, 1927 the Liverpool Daily Post and Mercury had an article which read:

`IN MEMORY OF A NOBLE WOMAN.

“KITTY WILKINSON” PRIZE FOR GIRLS’

`The memory of Kitty Wilkinson, the heroic woman of humble birth, who performed great public service by the institution of washhouses in Liverpool during the cholera plague of 1832, will be more firmly and widely held in admiration as a result o f a gift-book scheme which the Lord Mayor (Mr F. C. Bowring) has offered to finance. By this scheme a book of the life of Kitty Wilkinson will be presented annually in every senior girls’ school in the city.

` The prize will be awarded to elementary school girls who, in the opinion of their teachers, have earnestly and successfully tried to carry out the direction `Thou shall love thy neighbour as thyself’. The book is the `Memoir of Kitty Wilkinson’ edited by Mr Herbert H. Rathbone, with a foreword by Mr T. P. O’Connor, M.P…. The book is published by Henry Young’s at two shillings and sixpence. Two thousand copies are to be reserved from sale, and from these there will be presented annually in every senior girls’ school in the city a copy of the Memoir to the girl considered most fit to receive it. The Lord Mayor has generously offered to provide the funds necessary to carry out this suggestion.

`The Council of Education are to be asked to receive and hold the proceeds of the sale of the book to the public, with power to use such proceeds for the purpose of printing a fresh edition when the 2,000 set aside for prizes are exhausted – that is in about 10 years time. Power will be given to the Council to use the money for other purposes, according to their discretion, as it is thought not wise to legislate in a matter of this kind too far ahead. The prize-books will, it is suggested, bear the inscription:

KITTY WILKINSON PRIZE

INSTITUTED IN THE YEAR 1927

by

The Lord Mayor of Liverpool F. C. Bowring Esq., J.P.

Presented to

…………………………………………..

for having earnestly endeavoured to act in accordance with the direction ‘Thou shall love thy neighbour as thyself ‘.